Asphalt changes to gravel as soon as the road turns to Sotk village. There is no sound, only the rustling of trees. And a dog walking silently, collapsed roofs, locked doors, pieces of glass, and countless fragments of shells.

In the distance, people could be seen: one silently leaning against the wall, one sitting on the stairs of the house, which a few days ago had standing walls, cleanly washed windows, from which a view opened to the garden with flowers. But a few days ago, when, I remember, there was a full moon, and there was probably a full moon over the head of an enemy artilleryman, it was decided that shells would be hung on the roofs of the houses of peaceful people getting ready to go to bed, in the gardens, in the middle of the village, and everywhere.

Sotk is one of the border settlements of Gegharkunik that the enemy shelled mercilessly. When walking here, at every step left and right, buildings with traces of war come across, and not only houses. Before returning to the houses, the Geghamasar community hall, located in Sotk village, was also targeted and damaged. There are traces of debris on the outer walls, broken doors, and pieces of glass in the corridors, and in the yard.

The administrative head of Sotki, Sevak Khachatryan, is near the building of the community hall, and he is constantly walking around the village. He remembers well that the first strike in the direction of the village was at night, at 00:05, then they realized that “something is wrong”, and the intense shelling began, essentially not stopping that night and the following days.

“Whoever had a car among the residents got out, came back, and took the others, and by 4 am most of the residents were evacuated,” he says.

According to his information, Sotk has about a thousand inhabitants. Although most of them have been evacuated now, only men come to the village to feed their animals, they go back to temporary settlements, one to Vardenis, one to Martuni, so, in a word, to neighboring settlements. But Khachatryan says that there are already families who spend the night in the village. He and his parents stay in the village. At the moment, there is no electricity in the village, but, he says, the issue of electricity and gas will be resolved soon.

The administrative head of the village also notes that the enemy has not advanced in the direction of the village, and we and they are in the same positions. According to him, there was no shooting after the ceasefire.

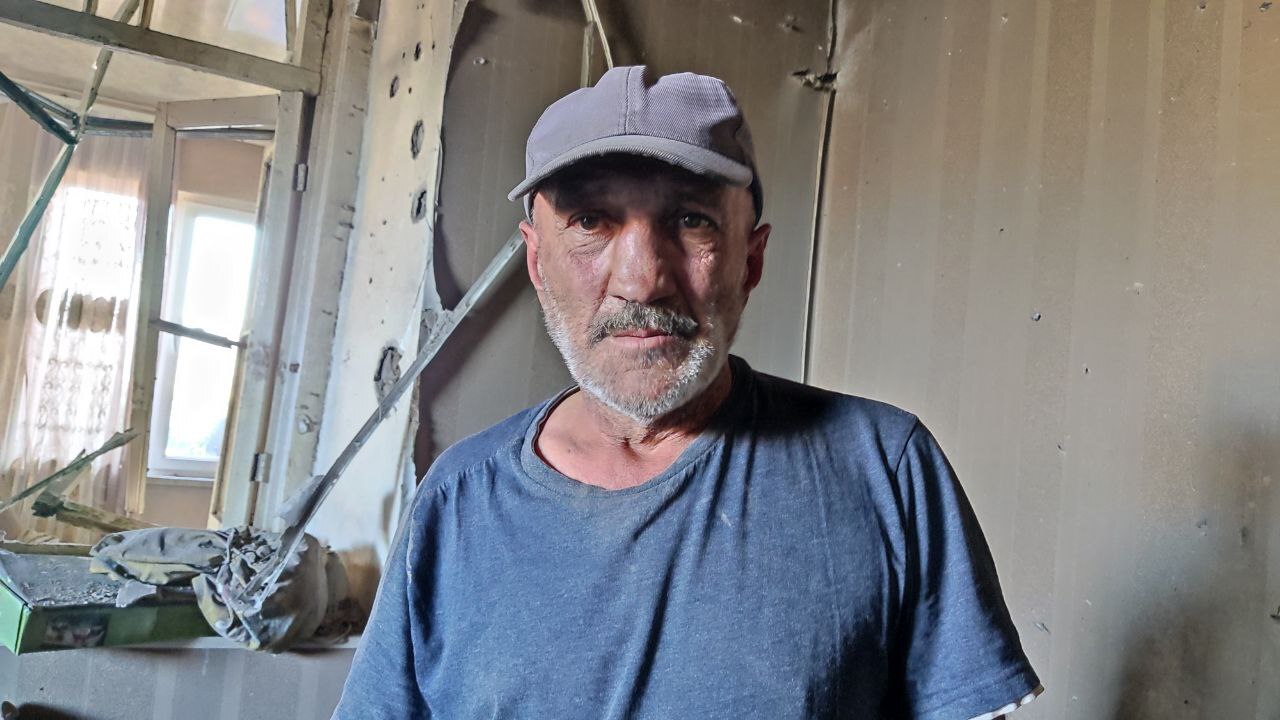

I meet an old man called Rafik rushing to his car, I managed to ask a couple of questions (it’s hard to ask questions to people who are going through all this). He says that only 11 shells exploded near his house.

“The house is full of smoke, eleven mines are near my house alone. Now the Russians are here,” he says and gets into the car. Rafik managed to get the children out of the village, fortunately, they were not injured.

Rafik

Andranik Simonyan, one of the residents of the village, took his family out at night, and he stayed behind. Andranik also took part in the 44-day war, and now what happened in the previous days is, of course, painful, but maybe it doesn’t seem that terrible anymore. They ask him from the side, “You got injured that day, didn’t you?” He keeps his eyes down and says, “No!”, but the others say that he got injured.

Andranik

Fellow villager Melkumyan Vano also joins the conversation. I ask him what he thinks, how this difficult problem will be solved, and he answers: “Well, the whole village wants to know how it will be. We have a cemetery here, we have something, it’s our land and water, we don’t want to go, they want to know the answer to that question. It’s a complicated, complicated situation.” Andranik goes on: “At least the state will support the one whose house is destroyed, to some extent, the should help.”

Then Vano accompanies his fellow villagers to the houses of his relatives, which were damaged and destroyed by shelling. Before reaching the houses, he shows the marks of the bullets one by one, a hole was created in the garden of one of them, a thick metal rod was broken by a fragment of one, a wall was destroyed in one place…

I take a picture of the shattered shelves that has fallen from the ground, and then I notice the couple sitting near it on the stairs of the yard. They sit silently, they don’t say anything. I approach, afraid to disturb their silent pain. “Tell me, how did it happen?” I dare to ask, “were you at home?”

Meline nods: it’s good, they weren’t injured, they managed to get out.

Meline

I ask about the expectations, Emil says: first of all, let them give the bodies of our victims, let no one die, and the destroyed houses can be repaired, and even if they don’t get repaired, once again, the important thing is the lives of our boys.”

Emil

Valery Poghosyan’s house is next to Emilents house. The projectile fell into the house, and the house collapsed. “I heard you say, ‘Come on, it’s a war, let’s go out.’ I told my mother, my wife: “Wait, I’ll run to get the car. I ran, bring the car, we got in the car, we left,” says Valery, standing in the ruins, next to her mother, Mrs. Greta, who can’t stay there anymore and leaves. She leaves the room, which does not even look like a room.

Valery

The impressions from Sotk are heavy. The apples have grown on the trees, the dogs are sitting lonely in the yards, and there are no people, no children playing, no elders cultivating the garden.

But in that bitter air, perhaps in the corner of every damaged house, there is hope that they will come to remove the locks from the doors, put new glass in the window, wash the clothes, clean the floor, water the flowers, feed the dogs, sweep the yard, look at the sky, be amazed by its blue, teach the children the names and the locations of constellations, countries on the map, not worrying that they may not know our place in another part of the world, then make apple dry fruits, put it in children’s hands to chew on their way to school. In a word – they hope to live.

Hayarpi Baghdasaryan